WORKSHOP

For Teaching to Cross With No Stop Sign or Traffic Signal

Click here for information about future workshops.

On April 25, 2009, I did a workshop in Silver Spring, Maryland to help O&M specialists become more comfortable teaching students about crossing where there is no traffic signal or stop sign.

Eight O&M specialists from Virginia and Maryland and two O&M interns participated. They had read the basic material you have hopefully already read, which is:

On April 25, 2009, I did a workshop in Silver Spring, Maryland to help O&M specialists become more comfortable teaching students about crossing where there is no traffic signal or stop sign.

Eight O&M specialists from Virginia and Maryland and two O&M interns participated. They had read the basic material you have hopefully already read, which is:

We met in front of a retirement home that had all the facilities we needed for our in-the-street workshop. That is, it had a parking lot and some bathrooms!

You can be a secret observer of the workshop, through the descriptions and simulated photos of the exercises that we did.

For the photo simulations, my son Paul and his wife Jomania posed as the O&M workshop participants, and my husband Fred took the photos.

We did this on Mother's Day -- having them all work so hard to help demonstrate the workshop exercises

was my best Mother's Day present ever!

If you want to do the exercises too, you might want to find a partner -- the exercises can each be done alone but at the workshop, the participants paired up for many of them.

Enjoy!

Photo courtesy of Sally Gannon

Getting started

Getting started

At the workshop, after we had assembled in front of the building and introduced ourselves, I gave them their handouts and said:

"The skills we will cover today are all included in the list of skills needed to cross streets (see handout).

Some of these are listed under 'general street-crossing skills' -- these skills are needed for crossing any streets.

Others are listed under 'Crossings with no traffic control' and they are needed only at crossings with no stop sign or traffic signal."

"We will cover teaching students to:

- determine width of street and understand crossing time (direct link)

- recognize situations of uncertainty for gap judgment (direct link)

- understand about masking and blocking sounds (direct link)

- judge speed and distance of vehicles (direct link)

- glance / scan for vehicles" (direct link)."

Photo courtesy of Sally Gannon

Determine width of street and understand crossing time

CHOOSING A SITE:

CHOOSING A SITE:

The first exercises can be done in parking lots and/or quiet streets that aren't sloped enough to recognize when you reach the middle.

If you use a parking lot, be aware that parking spaces are often only about 8 feet wide, whereas the typical moving lanes in streets are about 10-14 feet wide.

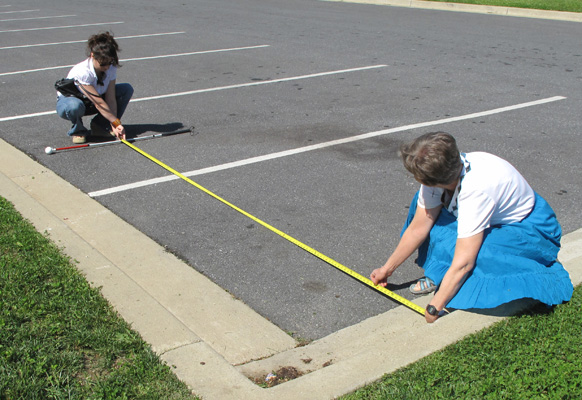

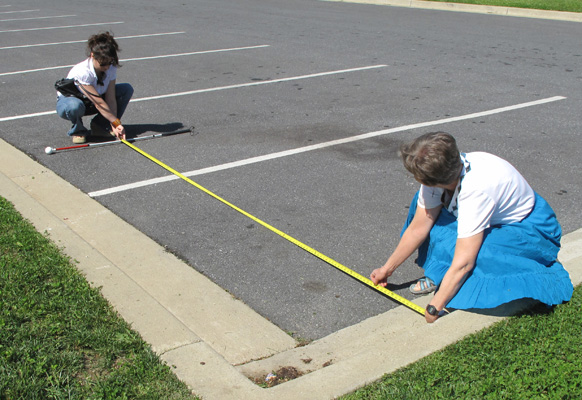

For example (to the left, top photo), one of the lanes on a major state road measured 12 feet across,

and the lanes of a typical two-lane residential side street measured 13.5 feet wide (lower left).

(Please don't think badly of me just because I stayed close to the curb and sent my loved ones out into the street with the tape measure!).

(Please don't think badly of me just because I stayed close to the curb and sent my loved ones out into the street with the tape measure!).

I prefer to do these exercises in quiet parking lots where we can approach and step off from a curb, as shown in the photos below.

Jomania and I used canes to mark two 12-foot-wide lanes in the parking lot to show you the comparative width of lanes and parking spaces.

To tell you the truth, I had never before measured the lanes and marked the parking lot. I normally estimate or pace the distance and, if needed, I look for natural markings like cracks or discolorings, or mark it with little stones.

To tell you the truth, I had never before measured the lanes and marked the parking lot. I normally estimate or pace the distance and, if needed, I look for natural markings like cracks or discolorings, or mark it with little stones.

But I had fun thinking of ways you should NOT mark the lanes. Do NOT to use spray paint,* and do NOT ask workshop participants to use their bodies to mark the lanes -- unless it is Mother's Day, and you can convince your children to do it for you!

* No parking lots were harmed in the production of this photoshopped demonstration.

Finally, we are ready to get serious for our first exercise!

EXERCISE:

For congenitally blind children, we need to explain that a lane is a space provided for vehicles to move, and explore the various sizes of vehicles (and their mirror extensions!) in parking lots to understand

how much space they need and how wide the lanes must therefore be.

EXERCISE:

EXERCISE:

Goal: understand about how far you need to walk to cross each lane.

Wear a blindfold and walk across the lanes in a street or marked in the parking lot, while your partner reports when you have reached the end of the first lane, and when you reach the end of the second lane, and so on.

EXERCISE:

Goal: Be able to accurately determine when you've walked across a lane or lanes.

After you think you understand how wide the lanes are (without counting steps!) walk across the lanes with the blindfold on again, but this time report when you think you have reached the end of the first lane, then the second lane, etc. Your partner will give you feedback as to your accuracy.

EXERCISE:

Goal: Understand your own crossing time for streets of

various widths.

Have your partner time you as you cross a street or a designated area in the parking lot. When I use a parking lot, I like to have them cross to a curb from a distance I have measured (such as two lanes, or the width of a street that we are analyzing, as I did in Vignette #1).

After you know how many seconds you need to cross, both of you stand at the edge of the street or designated area. You will then imagine in your mind that you are crossing the street or designated area. Tell your partner when your imaginary crossing begins so he can start his stopwatch.

Then tell him when you think you have reached the other side, and he will stop the watch and report how accurately you guessed your crossing time.

NOTE: Avoid counting seconds! Just as it is important for students to learn to use their "muscle memory" to understand distances rather than counting steps, it is important that they have a "mental" understanding of time needed to cross, rather than having to rely on counting seconds.

If you underestimated the time (that is, you thought you would be on the other side before the stopwatch indicates you'd be there), join the club! Most people underestimate it, often by half, as was done by the student in Vignette #1.

If you underestimated the time (that is, you thought you would be on the other side before the stopwatch indicates you'd be there), join the club! Most people underestimate it, often by half, as was done by the student in Vignette #1.

If you were not accurate, have your partner use his stopwatch to time an imaginary crossing for you. He might say, "Imagine if you start crossing 'NOW' (he starts his stopwatch), you're crossing,

you're crossing, now you're in the middle, still crossing .... NOW you've reached the other side." Then you try again to estimate when you would reach the other side during your imaginary crossing, and see if you do better.

CHOOSING A SITE:

CHOOSING A SITE:

Find a street that has 3-4 lanes going in one direction (it can have traffic going the other direction also -- stand on the side with the most lanes).

It is best when the vehicles pass sporadically rather than in large groups, so the student can hear them one at a time.

For the workshop, we walked to a street that has 3 lanes going one direction and two in the other,

and for these photos, the street has 4 lanes going in one direction, and 3 in the other.

EXERCISE:

Goal: Be able to determine how far away (that is, in which lanes) the vehicles are as they pass along the street

With eyes closed or blindfolded, stand at curb and listen to the passing cars as your partner tells you which lanes they are in.

At the workshop, I stood behind all 10 participants. Before each vehicle arrived in front of us, I told them in which lane it was approaching, so they could hear how cars sound in that lane.

When you think you can hear the difference between the lanes, start to report to your partner which lanes you think the cars are passing in.

At the workshop, the participants all felt they could hear the difference in the lanes in less than 5 minutes.

At that point, I didn't report which lane the vehicles were in until after they had passed, so that the participants could guess which lane and then see if they were correct.

Before long, they all reported that they could accurately judge vehicles in all 3 lanes.

My clients usually learn to distinguish vehicles in the first 3 lanes within about 10-20 minutes also. Most are unable to reliably discern vehicles beyond the 4th lane, even after prolonged practice -- they can only recognize that the vehicles are "very far off" (further than 4 lanes away).

Uh-oh! By this time, Paul and Jomania had been posing for Mom's photos much longer than they had expected, so it was time to give them a break.

They came up with lots of ways to use canes besides marking the lanes in the parking lot!

It's SHOW TIME!

Finally, we have the preliminary concepts -- now we're ready to hit the road, see the real world!

The workshop participants put on their blindfolds and piled into some of their cars to go to analyze our first site.

If you do your own workshop, please make sure that your drivers are not wearing blindfolds!

Recognize situations of uncertainty for gap judgment

That is, recognize situations where you can't hear (see) the traffic well enough

to know whether or not something is coming

that could reach you before your finish your crossing

EXERCISE:

EXERCISE:

Goal: Determine width of an unfamiliar street.

At the workshop, I led the caravan of cars with participants to this street, which they had never seen. They got out of the cars and listened to the traffic.

Before your students can analyze a street to determine how wide it is, they need to understand typical layouts of streets.

For example, usually streets are symnetrical. Some have parking lanes on one or both sides, and at busy intersections there often is one more lane entering than leaving the intersection because a left-turning lane has been inserted.

The participants noticed that the traffic going right to left was in the second lane, and they heard traffic going the other way in the first lane, so they figured it was two lanes wide.

It sounded as if there was room for a car to park between the curb and the nearest moving traffic, so they

figured there were two moving lanes (one going each direction) with room to park on both sides. And they were right!

NOTE: During the time that students learn to recognize situations of uncertainty for gap judgment (as described below), they can learn to notice when something is blocking the sound of the traffic, as the vehicle in this photo is doing (the degree of blockage depends on how tall the vehicle and they are).

EXERCISE:

Goal: Recognize situations of uncertainty for gap judgment.

Now began the real essence of the workshop -- learning to recognize situations where you can't hear the traffic well enough to know whether or not it's clear to cross!

CHOOSING A SITE:

Students should have opportunities to analyze 3-4

situations, with at least one situation where

they can hear (or see) all the vehicles well enough to know when it is clear to cross, and at least one situation

where they can't, so they can learn to recognize which situations are which.

Each site should have steady conditions. For example, if the student is using hearing, you should avoid places with ambient noises that increase and subside during your exercises.

Ideally, it will be a place with plenty of quiet gaps in traffic, and plenty of approaching traffic.

The session will be longer if there are long periods with no traffic, and/or long periods without any quiet.

At the workshop, we went to the site I had chosen.

We started to record everyone's crossing time but there were too many people, so we used a crossing time of 7 seconds.

For your students, of course, you would not use the average pedestrian walking speed, you would time their crossings to make sure they understand how long they need to cross.

We started to record everyone's crossing time but there were too many people, so we used a crossing time of 7 seconds.

For your students, of course, you would not use the average pedestrian walking speed, you would time their crossings to make sure they understand how long they need to cross.

The

dialog went something like this:

Dona: It is important to tell you, as a student, that there are places where you cannot hear the traffic well enough in both directions to be sure there is nothing coming that could reach you before you finish your crossing.

I call those "situations of uncertainty for gap judgment" because in those situations, you don't know whether there is time to cross before another car comes.

I want to see if you can figure out whether this is a "situation of uncertainty for gap judgment." It is quiet here now, so I want you to listen to the traffic when it comes, and see if this street seems like one of those places where you can't tell if something is coming or not, or whether you can hear all the vehicles from both directions well enough that when you hear nothing coming, you know it is clear to cross.

Participant: Do your students usually understand what you mean?

Dona (laughing): No! I haven't figured out how to say it so they understand. Often I'll explain it and

then, when it gets quiet they say, "I'd start to cross now!" So I say, "well, then, let's see what happens when a car comes."

So, when the student hears a car coming I say, "For example, do you think that if you had started to cross just before you heard that car (that is, while it was still quiet), the driver would have had to slow down for you? Or would you have made it to the other side before he got here?"

[Just then, we heard a car approaching.]

[Just then, we heard a car approaching.]

Dona: Oh, what luck, here comes something now!

[A minivan passes slowly by.]

What do you guys think? Would you have made it across if you had started just before you heard that car?

Participants: Yes, plenty of time.

Dona: Great, you have the idea. Of course that was was pretty easy to hear.

Now I want you to listen to as many cars as you need in order to guess whether you can hear all the cars -- from both directions -- well enough here to know it is clear to cross whenever it is quiet.

Participant: But aren't we supposed to time the cars?

Dona: Not yet -- we'll do that later, in order to test your judgment.

First, we want to know how well you / your students can assess the situation, and then we test your judgment / your students' judgment by timing the vehicles.

The goal is for your students to be able to assess situations just by observing, without counting and timing -- the timing is just used to give them feedback to help them improve their judgment, if needed.

[The participants listened to the traffic for a while, and judged that they can hear the cars well enough from both directions to know that it is clear to cross whenever it is quiet.]

Dona: Great -- now we'll test your judgment with the TMAD.

Wait until it is quiet, then start your stopwatch as soon as you hear something that might be a car coming from either direction. Stop the watch when the car passes in front of us.

Dona: Great -- now we'll test your judgment with the TMAD.

Wait until it is quiet, then start your stopwatch as soon as you hear something that might be a car coming from either direction. Stop the watch when the car passes in front of us.

It became quiet, then we heard a vehicle coming from the right. Most participants started their stopwatch immediately but some waited for a few seconds.

Partipant: I heard it 12 seconds away.

Dona: Ah, that was more than enough time to cross the street. If you can hear all the vehicles that well, you will know that you were right -- it is clear to cross whenever it is quiet.

Do you think that car was one of the "worst cars"? That is, one of the more difficult cars to hear?

Participants (hesitating): Not sure. What do you mean? [Some participants look at their stopwatch.]

Dona: Oh, I didn't want to know if the time for that car was short. What I meant is that, as the car passed, did it seem fast and quiet, or slow and loud?

Participant: Well, it was a slow, loud truck, so I think it was not one of the worst cars.

Dona: I agree. So that means that other cars will probably reach us in shorter time once we first hear them.

What about the rest of you? Did you all hear that truck 12 seconds away?

What about the rest of you? Did you all hear that truck 12 seconds away?

Participant: My stopwatch says only 9 seconds.

Dona: Did you start the stopwatch the instant that you thought there might be a car? Or did you wait to be sure it was a car?

Participant: I waited to be sure.

Dona: Ah, this happens often with my students -- I can hear a car coming but they don't report hearing it until a few seconds later. It turns out they were waiting to be sure it was a car before reporting.

I explain to them again that I want them to report the INSTANT that they hear something that they think MIGHT be a car.

Sometimes I explain that I want to know as soon as they hear anything that would make them hesitate about crossing because they think it might be a car.

Then, when they report hearing something that turns out not to be a car, I praise them and thank them for reporting it and tell them that's exactly what I want them to do. Then we reset the stopwatch and listen again.

Okay, let's do that -- please reset your stopwatch and start listening again.

Okay, let's do that -- please reset your stopwatch and start listening again.

[After it got quiet, the next approaching vehicle was from the left.]

Participant: I heard that 10 seconds away.

Dona: How many seconds do we need for the cars from that direction?

Participant: Half as much -- about 4 seconds -- because you're out of the way of those vehicles after crossing half the street.

Dona: Right. So you heard that car more than twice as far as you need to.

So even if it is not one of the worst cars and you don't hear all the cars as well as you heard that one, there is such a huge safety margin that

when it is quiet, it is extremely unlikely that there will be a car from the left that we are unable to hear until it is less than 4 seconds away.

We timed our detection of several other cars, and were able to hear all of them with more than enough time.

We timed our detection of several other cars, and were able to hear all of them with more than enough time.

Dona:

Well, it's getting late and we need to move on to the second site, but if we were really testing a student's judgment as

to whether she can hear all the cars far enough to be sure that it's clear to cross whenever it's quiet,

we would continue to time her detection of the cars until one of the following happened:

1. when conditions are ideal (e.g. it is quiet), we find a car that the student couldn't hear (see) far enough away

(then we know she can't hear/see all the cars far enough to away to know it's clear to cross when quiet); or

2. we are satisfied that the student can hear all the vehicles well enough because either:

the student and instructor both agree we heard one of the "worst cars" from each direction, and

the student was able to hear even those well enough; or

the student can hear the cars SO much more than is needed that, even though there are probably cars

that are harder to hear than the ones we've observed, we both agree that there

is enough safety margin that we are confident all the cars can be heard well enough.

The next site was a residential street about the same width as the first, with an estimated crossing time of 7 seconds.

It didn't take long before we observed a car from the right that we did not hear until it was 6 seconds away.

It did not seem to be one of the "worst cars" -- it was not very quiet when it passed us and was not going very fast -- so the participants figured there might be cars that are heard with even less warning than this one was.

The cars cannot be heard before they are seen coming around the bend [left below] and they pass in front of us only a few seconds later [right below].

Although cars from the left could be heard further than the participants expected and much further than was needed to cross half the street, there was no need to spend more time analyzing this crossing.

It was clearly a situation of uncertainty for gap judgment because of the inability to hear (or see!) the cars from the right.

Although cars from the left could be heard further than the participants expected and much further than was needed to cross half the street, there was no need to spend more time analyzing this crossing.

It was clearly a situation of uncertainty for gap judgment because of the inability to hear (or see!) the cars from the right.

That is, when it is quiet, we don't know if something is coming that would have to slow down for us.

At this point, we talked about the level of risk, and alternatives.

They considered the risk of crossing as being low at that time, but would be high when traffic is frequent, like when people are coming home from work.

When it is quiet at those times, it would be fairly probable that a car is approaching which we couldn't hear, and which would have to slow down to avoid a collision.

And since the driver can't see the pedestrian until he comes past the bend, there would be a possibility that he wouldn't have enough warning to be able to stop, especially in bad weather.

Alternatives that they considered included crossing where they could hear better (such as further from the bend in the road), or avoiding the crossing by taking the bus to the end of the line and back. Getting help wasn't a useful alternative because

sighted people can not anticipate the vehicles any better than blind people can.

Masking and blocking sounds

Analyzing situations as we have been doing provides GREAT opportunities for students to learn the effect of ambient noise (masking sounds) and how the sounds of the approaching vehicles can be blocked by parked vehicles, hills, signs, etc.

At our first site, while timing our detection of cars, we were unable to hear one of the cars until it got very close. Someone started her stopwatch when she heard it. She stopped it when the car passed in front of us.

Participant: I heard that one only 4 seconds away.

Dona: Wow -- why do you suppose you couldn't hear it until it was so close, when you could hear all the other cars much further?

Participant: It wasn't quiet when I heard it.

Dona: Indeed! If it had been quiet, we would have heard it much further. Let's listen to how well we can hear cars approaching when there are cars receding.

[We noticed that whenever there was receding traffic still in the roadway, we were unable to hear other approaching cars until they were very close.]

Dona: I use observations like this, as well as timing, to help students understand the effect of masking sounds.

For example, we might hear one car from very far away and, when it passes, there is a second car right behind it that we can't hear until it is very close to us.

Or we might not be able to hear a relatively loud, slow truck until it gets very close because there was noise from receding cars, lawnmowers, etc.

Dona: I use observations like this, as well as timing, to help students understand the effect of masking sounds.

For example, we might hear one car from very far away and, when it passes, there is a second car right behind it that we can't hear until it is very close to us.

Or we might not be able to hear a relatively loud, slow truck until it gets very close because there was noise from receding cars, lawnmowers, etc.

When I ask students why we couldn't hear those vehicles until they got so close, often they don't know.

They are completely unaware of the effect of masking sounds, and weren't even aware that it wasn't quiet when we heard that vehicle.

Sometimes they suggest that maybe we couldn't hear that car because it is one of those "quiet cars" that they heard about, but I point out that the car itself was not quiet when it passed us.

I then explain that the reason we couldn't hear it earlier is because sounds -- any sounds -- can reduce our ability to hear approaching traffic.

Sometimes they don't believe that they can't hear well enough when there is an airplane overhead or a lawnmower in the distance.

Timing our detection of the approaching vehicles verifies that we can't hear them as far away as we can when it is quiet.

If we can't get good timing samples to compare because the changes in ambient sound are sporadic, I sometimes use a steady background sound from a tape recording of white noise (actually, it's a recording of my vaccuum cleaner!)

It is also important for our students to know how quiet it must be in order to hear the cars well enough.

Over the years, I've noticed that at some places, you can hear fine even when there is a lawnmower in the distance, whereas at other places it has to be absolutely pin-drop quiet to hear well enough.

This was verified when Rob and I did our study. We did some of our data collection at this very spot, measuring people's ability to hear 290 vehicles approaching here.

We also collected data at the place with the bend in the road where we went today, and also at a place with a hill.

The affect of ambient sound differed from site to site. For example, here at this site, it could actually get up to 40 dBA before there were any cars they couldn't hear well enough, whereas at the hill, they could hear well enough only when it was very quiet -- the slightest increase in ambient sound

greatly affected their ability to hear the cars at a distance.

So I like to make sure students understand how much ambient noise they can tolerate before they are no longer able to hear well enough [see "Effect of background noise"].

When we are in a place where we know it's clear to cross whenever it's quiet, like we are here, I may make some ambient noise with this tape recorder and say something like, "You can hear well enough when it's quiet here.

Can you still hear well enough when there is this much noise in the background?"

The student would listen to the traffic while the tape recorder makes the noise, and guess whether he can still hear the approaching vehicles well enough, and then we'd test his judgment with the TMAD again, like we just did.

Not only does this help the student realize how quiet it has to be in order to hear the traffic there, it also provides a second scenario without having to move -- at one site, you can have the student analyze two different situations (one with quiet, one with constant noise).

When we are in a place where we know it's clear to cross whenever it's quiet, like we are here, I may make some ambient noise with this tape recorder and say something like, "You can hear well enough when it's quiet here.

Can you still hear well enough when there is this much noise in the background?"

The student would listen to the traffic while the tape recorder makes the noise, and guess whether he can still hear the approaching vehicles well enough, and then we'd test his judgment with the TMAD again, like we just did.

Not only does this help the student realize how quiet it has to be in order to hear the traffic there, it also provides a second scenario without having to move -- at one site, you can have the student analyze two different situations (one with quiet, one with constant noise).

If you choose sites that have hills or bends in the road, or parked vehicles, students can also learn about blocked sounds of approaching cars.

They can experiment and see if they can hear better by moving away from or toward and beyond the obstacle / bend.

Judge speed and distance of vehicles

(see Timing Method for Assessing Speed and Distance of Vehicles or TMASD)

CHOOSING A SITE:

I like to use streets that are straight and flat, because if students can learn to judge the speed and distance of those vehicles, they can probably do it anywhere!

Those vehicles are most challenging because it is easier to judge the speed and distance of vehicles that are moving slightly across your path or down a hill than those that are approaching you head-on (thus it is easier to judge vehicles from the right than from the left because the ones from the right are not approaching you directly).

EXERCISE:

Goal: Be able to judge whether approaching vehicles are all far enough or slow enough to allow you time to cross.

We used the TMASD, which requires that we choose an arbitrary time. The workshop participants felt comfortable with a 2-second safety margin, so we chose 10 seconds as our arbitrary time (7 seconds crossing time, 2 seconds safety margin, and 1 second for the fudge factor).

Then they stood at the curb at the first site and watched vehicles approaching. When they thought that the nearest vehicle was about 10 seconds away, they started their stopwatch.

They stopped it when the car passed, and then noted how close they got to 10 seconds.

Some of the participants had judged it well the first time, and others started to improve their judgment after timing a few cars. We didn't do this exercise for very long because they seemed to understand how to do it.

I forgot to caution them that many students will simply start the timer every time the car passes a certain landmark, so the instructor needs to make sure they are actually trying to judge when the car will be about 10 seconds (or whatever the arbitrary number is) away.

But I did tell them that most people can become skilled with judging speed and distance within about 20-30 minutes of practice, but about a half dozen of my clients didn't improve. I've found that having binocular vision isn't necessary -- many people with vision in only one eye did very well with this task.

What seems to be necessary in that case is enough visual field to see what the vehicle as passing -- people with monocular vision and severely restricted visual field can't judge how far or fast the cars are.

If they can't tell how fast / far the cars are coming, they can choose a landmark that they judge is far enough away that if there are no cars between them and the landmark, there is enough time to cross.

You can assess and help improve their ability to judge how far that landmark must be, and their ability to scan to be sure there are no vehicles between them and the landmark.

Glance / scan for vehicles

(see "Scanning for cars")

We've been watching for traffic in only one direction at a time, but of course people can't do that when they prepare to cross -- they need to look in several directions.

So they need to watch the traffic only long enough to know the situation on that side before turning to look in the other direction.

Some people with visual impairments have special needs for glancing. People with severely restricted visual fields will need to scan slowly or they may miss seeing a car to their left.

People with central scotomas may need to hold their gaze long enough to see movement.

Regardless of the eye condition, once the student has become proficient at visually discerning the situation in each direction,

it is good to practice doing it by glancing and scanning.

For example, students who can judge the speed and distance of the vehicles well enough to know when there is still time to cross, and students who can see the traffic far enough away to know it is clear to cross whenever they see nothing coming,

should learn how to do it as quickly and efficiently as possible so they can check the situation in both directions.

CHOOSING A SITE:

These exercises are designed to practice discerning or judging traffic by glancing, so they should be done at the same site where the student learned to discern or judge traffic visually.

EXERCISE:

Goal: Be able to judge, with as short a glance as possible, whether approaching vehicles are far enough or slow enough to allow you time to cross.

Stand at the curb facing the street;

When the instructor gives the signal, turn and look to see whether there are any vehicles too close or too fast to allow you to cross;

Hold the glance only as long as necessary to make that determination -- as soon as you think you know, start a timer and turn back to face the street again;

Stop the timer when the car passes you, and see if you were right or not.

If you thought there was time to cross when you glanced, then the timer should show at least as much time as you need to cross that part of the street.

If you thought there was not enough time to cross, then the timer should show that there was less time than you need to cross that part of the street.

If you were proficient at judging the speed and distance of the cars when you could watch them approach but you were wrong when you tried to do it by glancing, then perhaps you need to hold the glance longer before you are able to make that judgment.

Try it again until you find out how long you need to hold your glance in order to make accurate judgments.

EXERCISE:

EXERCISE:

Goal: Be able to use as short a glance as possible (or scan as slowly as is necessary) to make sure no vehicles are visible.

Stand at the curb facing the street;

When the instructor gives the signal, turn and look to see if there are any cars, holding the glance only as long as necessary (or scanning as slowly as is necessary, if you have restricted visual fields);

Look forward again as soon as you think you know whether there are any cars coming, and report to the instructor.

The instructor will tell you if you were right or not. If not, you need to improve the glance either by holding it longer, or slowing your scan.

The instructor should have the student turn to look when conditions are most challenging (see "Scanning for cars" for more information).

The most challenging situation for people with severely restricted visual fields is when there is only one car visible and it is in the "blind spot," as shown in the photo to the right (Paul is wearing goggles that simulate a restricted visual field).

To avoid having the student realize there is a car there because he heard it, produce a steady sound that can mask the sound of the cars, such as playing a recording of white noise.

Self-Study Guide: what next?

If you are following the Self-Study Guide, then go back to Applications! WORKSHEET for Teaching Crossings Where There Is No Stop Sign or Traffic Signal.

If you've already read "Applications! WORKSHEET," you might want to go to the Self-Study Guide to see if you've read all the recommended pages.

If you've read all the recommended pages, then congratulations -- you are DONE!

Click here to find out how to get a Certificate of Completion.

Return to Applications! Worksheet for Teaching Crossings Where There Is No Stop Sign or Traffic Signal

Return to Self-Study Guide:

Preparing Visually Impaired Students to Assess and Cross Streets with No Traffic Control

Return to Home page

Although cars from the left could be heard further than the participants expected and much further than was needed to cross half the street, there was no need to spend more time analyzing this crossing.

It was clearly a situation of uncertainty for gap judgment because of the inability to hear (or see!) the cars from the right.

Although cars from the left could be heard further than the participants expected and much further than was needed to cross half the street, there was no need to spend more time analyzing this crossing.

It was clearly a situation of uncertainty for gap judgment because of the inability to hear (or see!) the cars from the right.

Dona: I use observations like this, as well as timing, to help students understand the effect of masking sounds.

For example, we might hear one car from very far away and, when it passes, there is a second car right behind it that we can't hear until it is very close to us.

Or we might not be able to hear a relatively loud, slow truck until it gets very close because there was noise from receding cars, lawnmowers, etc.

Dona: I use observations like this, as well as timing, to help students understand the effect of masking sounds.

For example, we might hear one car from very far away and, when it passes, there is a second car right behind it that we can't hear until it is very close to us.

Or we might not be able to hear a relatively loud, slow truck until it gets very close because there was noise from receding cars, lawnmowers, etc.

When we are in a place where we know it's clear to cross whenever it's quiet, like we are here, I may make some ambient noise with this tape recorder and say something like, "You can hear well enough when it's quiet here.

Can you still hear well enough when there is this much noise in the background?"

The student would listen to the traffic while the tape recorder makes the noise, and guess whether he can still hear the approaching vehicles well enough, and then we'd test his judgment with the TMAD again, like we just did.

Not only does this help the student realize how quiet it has to be in order to hear the traffic there, it also provides a second scenario without having to move -- at one site, you can have the student analyze two different situations (one with quiet, one with constant noise).

When we are in a place where we know it's clear to cross whenever it's quiet, like we are here, I may make some ambient noise with this tape recorder and say something like, "You can hear well enough when it's quiet here.

Can you still hear well enough when there is this much noise in the background?"

The student would listen to the traffic while the tape recorder makes the noise, and guess whether he can still hear the approaching vehicles well enough, and then we'd test his judgment with the TMAD again, like we just did.

Not only does this help the student realize how quiet it has to be in order to hear the traffic there, it also provides a second scenario without having to move -- at one site, you can have the student analyze two different situations (one with quiet, one with constant noise).

On April 25, 2009, I did a workshop in Silver Spring, Maryland to help O&M specialists become more comfortable teaching students about crossing where there is no traffic signal or stop sign.

Eight O&M specialists from Virginia and Maryland and two O&M interns participated. They had read the basic material you have hopefully already read, which is:

On April 25, 2009, I did a workshop in Silver Spring, Maryland to help O&M specialists become more comfortable teaching students about crossing where there is no traffic signal or stop sign.

Eight O&M specialists from Virginia and Maryland and two O&M interns participated. They had read the basic material you have hopefully already read, which is:

Getting started

Getting started CHOOSING A SITE:

CHOOSING A SITE:

(Please don't think badly of me just because I stayed close to the curb and sent my loved ones out into the street with the tape measure!).

(Please don't think badly of me just because I stayed close to the curb and sent my loved ones out into the street with the tape measure!).

To tell you the truth, I had never before measured the lanes and marked the parking lot. I normally estimate or pace the distance and, if needed, I look for natural markings like cracks or discolorings, or mark it with little stones.

To tell you the truth, I had never before measured the lanes and marked the parking lot. I normally estimate or pace the distance and, if needed, I look for natural markings like cracks or discolorings, or mark it with little stones.

EXERCISE:

EXERCISE:

If you underestimated the time (that is, you thought you would be on the other side before the stopwatch indicates you'd be there), join the club! Most people underestimate it, often by half, as was done by the student in Vignette #1.

If you underestimated the time (that is, you thought you would be on the other side before the stopwatch indicates you'd be there), join the club! Most people underestimate it, often by half, as was done by the student in Vignette #1.

CHOOSING A SITE:

CHOOSING A SITE:

EXERCISE:

EXERCISE:

We started to record everyone's crossing time but there were too many people, so we used a crossing time of 7 seconds.

For your students, of course, you would not use the average pedestrian walking speed, you would time their crossings to make sure they understand how long they need to cross.

We started to record everyone's crossing time but there were too many people, so we used a crossing time of 7 seconds.

For your students, of course, you would not use the average pedestrian walking speed, you would time their crossings to make sure they understand how long they need to cross.

[Just then, we heard a car approaching.]

[Just then, we heard a car approaching.]

Dona: Great -- now we'll test your judgment with the TMAD.

Wait until it is quiet, then start your stopwatch as soon as you hear something that might be a car coming from either direction. Stop the watch when the car passes in front of us.

Dona: Great -- now we'll test your judgment with the TMAD.

Wait until it is quiet, then start your stopwatch as soon as you hear something that might be a car coming from either direction. Stop the watch when the car passes in front of us.

What about the rest of you? Did you all hear that truck 12 seconds away?

What about the rest of you? Did you all hear that truck 12 seconds away?

Okay, let's do that -- please reset your stopwatch and start listening again.

Okay, let's do that -- please reset your stopwatch and start listening again.

We timed our detection of several other cars, and were able to hear all of them with more than enough time.

We timed our detection of several other cars, and were able to hear all of them with more than enough time.

EXERCISE:

EXERCISE: