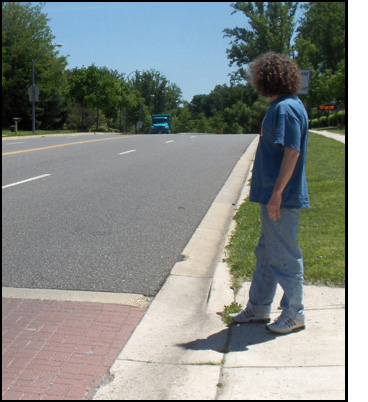

The student (represented in these photos by my son, Stephan) was 14 years old, and had a lot of vision.

I wanted to teach him to be able to recognize situations of uncertainty for gap judgment (that is, situations where he cannot predict whether or not it is clear to cross).

I chose the crosswalk in front of his school, where the street is 4 lanes wide, and there is no traffic signal or stop sign [see photo to the left].

I asked his mother to join us for the last part of the lesson.

The student (represented in these photos by my son, Stephan) was 14 years old, and had a lot of vision.

I wanted to teach him to be able to recognize situations of uncertainty for gap judgment (that is, situations where he cannot predict whether or not it is clear to cross).

I chose the crosswalk in front of his school, where the street is 4 lanes wide, and there is no traffic signal or stop sign [see photo to the left].

I asked his mother to join us for the last part of the lesson.

I started the lesson by taking the student to the crosswalk, and telling him that there are places where it is not possible for people to see the traffic well enough to know if there is something coming that would have to slow down to avoid hitting them.

I made sure he understood that this is true of everyone, and not because of any deficiency on his part.

I started the lesson by taking the student to the crosswalk, and telling him that there are places where it is not possible for people to see the traffic well enough to know if there is something coming that would have to slow down to avoid hitting them.

I made sure he understood that this is true of everyone, and not because of any deficiency on his part.

I said, "Oh, there is a good example! If you had started to cross just before you saw that truck -- that is, when you didn't see anything coming -- would the driver have had to slow down to avoid hitting you? Or would you have made it to the other side before he got there?"

I said, "Oh, there is a good example! If you had started to cross just before you saw that truck -- that is, when you didn't see anything coming -- would the driver have had to slow down to avoid hitting you? Or would you have made it to the other side before he got there?" I said "Great, thanks! Okay, now we are going to test your judgment and see if you were right.

To do that, we first need to find out how much time you need to cross the street. I have marked an area in the parking lot that is the same width as this street, so let's go there and time your crossing."

I said "Great, thanks! Okay, now we are going to test your judgment and see if you were right.

To do that, we first need to find out how much time you need to cross the street. I have marked an area in the parking lot that is the same width as this street, so let's go there and time your crossing."

We stood at the marker and I asked him to pretend he was crossing to the curb, and tell me when he starts (in his mind), then tell me when he thinks he finishes the crossing.

We stood at the marker and I asked him to pretend he was crossing to the curb, and tell me when he starts (in his mind), then tell me when he thinks he finishes the crossing.

He watched the traffic, and then said he saw a car coming. I started the timer, and then stopped the timer when the vehicle passed in front of us.

He watched the traffic, and then said he saw a car coming. I started the timer, and then stopped the timer when the vehicle passed in front of us.

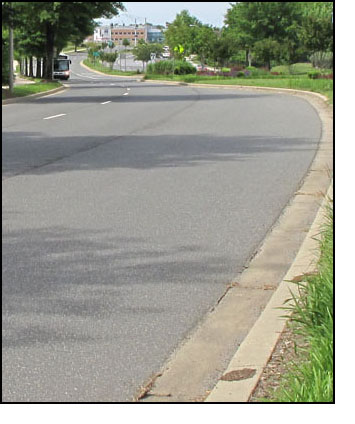

So there I was, standing with my client facing a street she'd have to cross to get to her community swimming pool.

The street looked like the one in the photo to the right -- it had two narrow lanes on each side of a wide, grassy divider, and half a block to our right the street ended at a driveway that went into her apartment complex.

So there I was, standing with my client facing a street she'd have to cross to get to her community swimming pool.

The street looked like the one in the photo to the right -- it had two narrow lanes on each side of a wide, grassy divider, and half a block to our right the street ended at a driveway that went into her apartment complex.

Then we walked to the corner of his community entrance on a busy two-lane street called Donaldson Road (shown to the right) to observe the traffic and talk about crossings.

He said he'd be safe crossing the entrance as long as he was in the crosswalk.

Then we walked to the corner of his community entrance on a busy two-lane street called Donaldson Road (shown to the right) to observe the traffic and talk about crossings.

He said he'd be safe crossing the entrance as long as he was in the crosswalk.

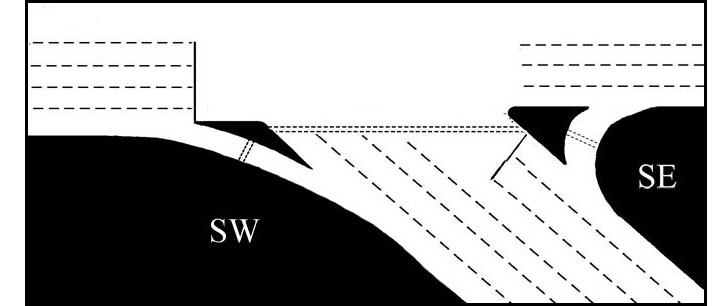

In two of those situations (the first two photos to the left), the road was straight and you could hear the cars at a distance even when you tried to block the sounds with a board.

In another situation (the last photo), no matter how quiet it was, you couldn't hear the cars until they came around a sharp bend in the road.

In two of those situations (the first two photos to the left), the road was straight and you could hear the cars at a distance even when you tried to block the sounds with a board.

In another situation (the last photo), no matter how quiet it was, you couldn't hear the cars until they came around a sharp bend in the road.

However in at least one situation (when traffic was coming over a hill, as shown in the photo to the left), that same increase in ambient sound dramatically reduced the ability to hear the cars.

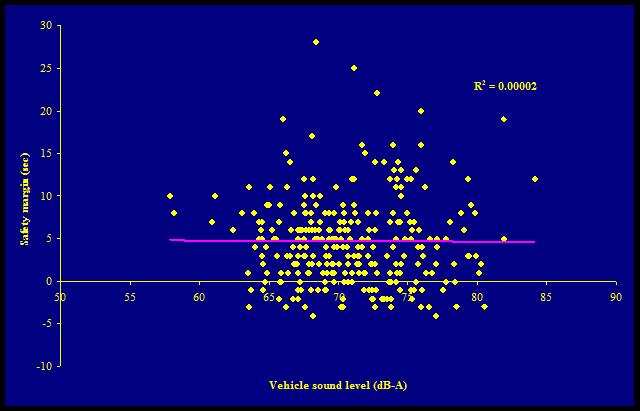

Click here to see the graph showing how the level of ambient sound at each of the 6 situations affected the ability to

hear the vehicles, as measured by the average "safety margin" -- notice how the line of the safety margin is dramatically reduced for the "hill" situation between 38 and 40 db(A) (it is also reduced for the "trees" situation but that varies wildly and randomly as the background noise increases).

However in at least one situation (when traffic was coming over a hill, as shown in the photo to the left), that same increase in ambient sound dramatically reduced the ability to hear the cars.

Click here to see the graph showing how the level of ambient sound at each of the 6 situations affected the ability to

hear the vehicles, as measured by the average "safety margin" -- notice how the line of the safety margin is dramatically reduced for the "hill" situation between 38 and 40 db(A) (it is also reduced for the "trees" situation but that varies wildly and randomly as the background noise increases).

Freaky problem

Freaky problem Real-life situation:

Real-life situation:

So, what the heck can we do about these situations?

So, what the heck can we do about these situations?

In our study of the ability of blind people to hear approaching vehicles at crossings where there is no traffic signal or stop sign, Dr. Rob Wall Emerson and I recorded the detection of 805 vehicles among 6 different road features, such as straight, curved, hills, etc. (see article).

We measured the speed and the sound level of the vehicles as they passed, as well as the ambient sound level (how loud the background noise was) at the time they were heard.

In our study of the ability of blind people to hear approaching vehicles at crossings where there is no traffic signal or stop sign, Dr. Rob Wall Emerson and I recorded the detection of 805 vehicles among 6 different road features, such as straight, curved, hills, etc. (see article).

We measured the speed and the sound level of the vehicles as they passed, as well as the ambient sound level (how loud the background noise was) at the time they were heard.