NOTE: Click here for the text from the Diary that relates to these photos.

Click here for the story of Mito Kosei's mother when the bomb fell in Hiroshima.

As we entered the Peace Garden, we were approached to sign a petition to prevent a Constitutional change that would allow Japan to wage war with other countries for reasons other than defense.

Afterwards, the volunteers bowed and thanked us for signing the petition.

I was very moved by the earnest peace-making efforts of these people, and asked for a group photo with Stephan. The Peace Garden and the A-bomb Dome are in the background.

Memorials overlook the river by the Peace Garden.

The plaque below shows the "A-bomb Dome" before and after the bomb; the reconstruction work; and an overhead view of the Peace Garden.

The plaque above reads:

"The building now known as the A-bomb Dome was designed by Czech architect Jan Letzel and completed in April 1915. With its distinctive green dome, this magnificent building was soon a beloved Hiroshima landmark.

"The hall was used to display and sell prefectural products. The offices provided market research and consulting for … commercial enterprises, but its galleries also served as venues for art exhibitions, fairs, and a variety of cultural …. As the war lengthened and intensified, the hall's … activities dwindeled. By April 1944, it was [used by government offices such as Public Works, Lumber Control, etc.]

"At 8:15 a.m. August 6, 1945, an American B29 bomber dropped an atomic bomb, the first atomic bombing in human history. The bomb exploded approximately 600 meters above and 160 meters to the southeast of the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall. The building was crushed and gutted by fire. Everyone in the building died immediately.

"However, because the blast came from almost directly above, some of the walls of the building remained standing, leaving enough of the building and iron structure at the top to be recognizable as a dome.

"After the war, the badly damaged skeletal remains of the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall came to be known as the A-bomb Dome.

"For many years opinions about the Dome were divided. Some felt it should be preserved as a memorial to the bombing, while others, calling it a dangerously dilapidated structure that evoked painful memories, advocated its destruction.

"Gradually, as the city was rebuilt and other A-bombed buildings vanished, the desire to preserve the Dome gathered strength. In 1966, the Hiroshima City Council passed a resolution declaring that the A-bomb Dome would be preserved in perpetuity. This led to a campaign to raise the funds required to physically preserve the Dome. Donations poured in from those who wished for peace in Japan and overseas. The first preservation project was implemented in 1967.

"Subsequently, several preservation projects have been carried out to ensure that the Dome will always look as it did immediately after the bombing.

"In December 1996, the A-bomb Dome was formally registerd on the World Heritage List as a historic witness to the tragedyof human history's first use of a nuclear weapon and as a university peace monument appealing for the abolition of nuclear weapons and the realization of … world peace.

"To help protect the Dome, the national government designated the area around it a historic site under the Cultural Properties Protection Act, with a larger area … around Peace Memorial Park set aside as a buffer zone…"

The A-bomb Dome building.

A Japanese woman, her husband and their children visit the Peace Garden.

Stephan and visitors view the remains of the building.

This memorial statue combines features of Christianity (wings of an angel), Buddhism (a Buddhist head) and Shinto (a belt with a long tassle).

Standing at the point marked as ground zero, we met Mito Kosei, the youngest survivor of the bomb, who gave us a tour of the Peace Garden. Behind Mr Kosei is a clinic, which was rebuilt by the doctor, who happened to be away at the time of the bomb.

Click here for more in the Diary from Asia about Mr. Mito Kosei as he guided us through the Hiroshima Peace Park.

Click here for the story of Mr. Mito Kosei's mother when the bomb fell in Hiroshima.

Mr. Mito shows us a cemetery that survived the bomb. Some markers were broken by the bomb [below, right], and others showed the effect of the bomb (the corners of the base shown in the two bottom photos were whitened by the blast and felt rough, whereas under the marble flowers the stone was not affected).

The plaque below reads: "Fuel Hall (approx. 170 meters from the hypocenter)

"This building was constructed in 1929, originally housing the Taishoya Kimono Shop. In June, 1944, as World War II intensified and economic controls became increasingly stringent, the building was purchased by the Prefectural Fuel Rationing Union.

"At 8:15 a.m. on August 6, 1945, the explosion of the atomic bomb about 580 meters above the hypocenter destroyed the building's concrete roof. The interior was also badly damaged and gutted by ensuing fires, and everyone inside was killed except one person in the basement who miraculously survived.

"The building was restored soon after the war and used as the Fuel Hall. In 1957, the Hiroshima East Reconstruction Office, which became the core of the city's reconstruction program, was established here."

According to Mr. Mito, the man who survived was in the basement looking for some documents. He lived another 40 years.

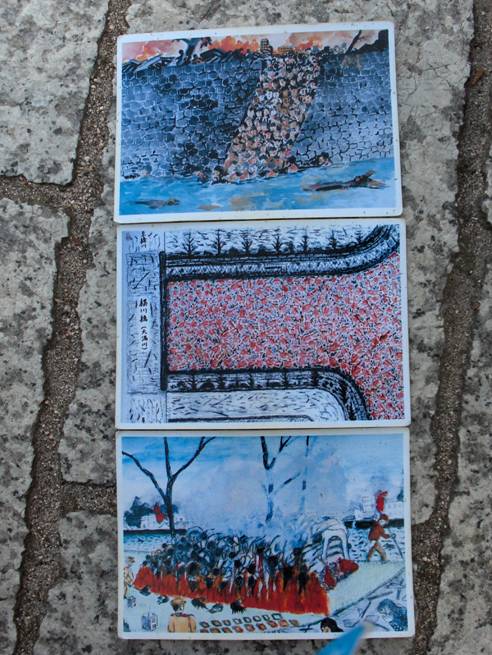

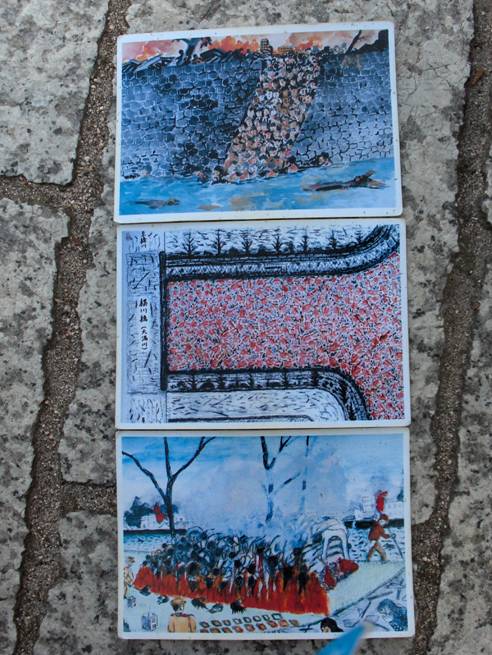

Drawings by the survivors depict what happened after the bomb [left].

Those who survived inhaled radioactive material, which makes every cell in the body crave water. The first picture [top] shows the people streaming down the stairs on the riverbank to drink.

They all died as their internal organs were destroyed, and the river became filled with bodies [middle picture], which eventually sunk and were very difficult to retrieve.

Since everything had burned after the blast, there wasn't enough wood left to cremate them properly [bottom drawing].

The ashes of the bodies were buried in a mound that resembled the burial mound of an Emperor (which did not please some of the survivors, who felt that it was the stubbornness of the Emperor that caused the Americans to bomb them).

Japanese school children visit a memorial depicting a large turtle. Turtles and cranes are symbols of long life in Japan.

The balls on top of this grave marker were blown away by the blast, and then blown back by the wind that resulted from the vacuum of air.

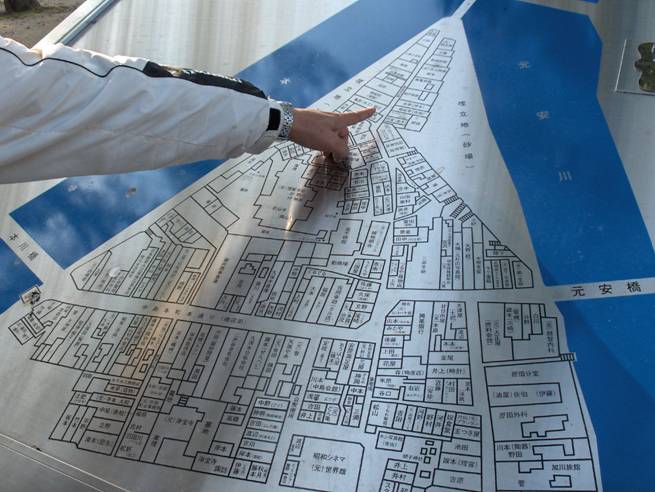

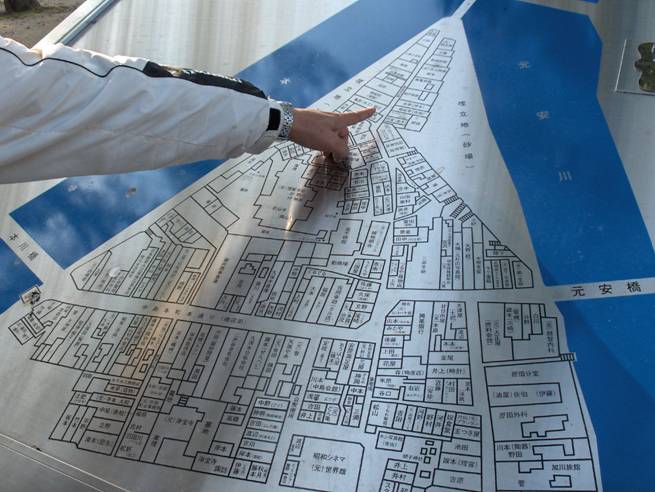

A map of the city was created from the memory of the survivors. Some lots are empty, as no one still alive could remember what or who was there.

The names of people living in Hiroshima are recorded from the memories of the survivors, since all records were destroyed. Many people are recorded only by their last name or no name at all, because no one who knew them survived.

A memorial [left] was dedicated to the children who were killed by the bomb. Thousands of children had been brought from surrounding schools and were working to strengthen the road, and all were killed.

One child who initially survived the blast became ill from radiation sickness, and decided to make 1,000 paper cranes (a symbol of longevity) in hopes of getting better. She had made 1,500 by the time she died.

The cases behind the monument hold many thousands of paper cranes, given by the children of Japan in ceremonies like the one shown in the photographs below. One of the people I later met in Japan said she remembered participating in this ceremony as a child, and it was a frightening experience for her.

Before presenting the paper cranes, students read to the group in front of the monument [shown above].

One of the children then presented a string of paper cranes that they have made [left]. . .

. . . while the others watched [photo below, left].

Two children then rang the bell [photo below, right].

Mr. Mito shows some of the cranes that have been donated by school children and displayed in the cases.

This memorial is dedicated to a doctor who donated medical supplies to help the victims of the bomb. When those supplies ran out a month later, the doctor's request for more supplies was thwarted by those who didn't want to publicize the fact that so many people suffered for so long as a result of the bomb.

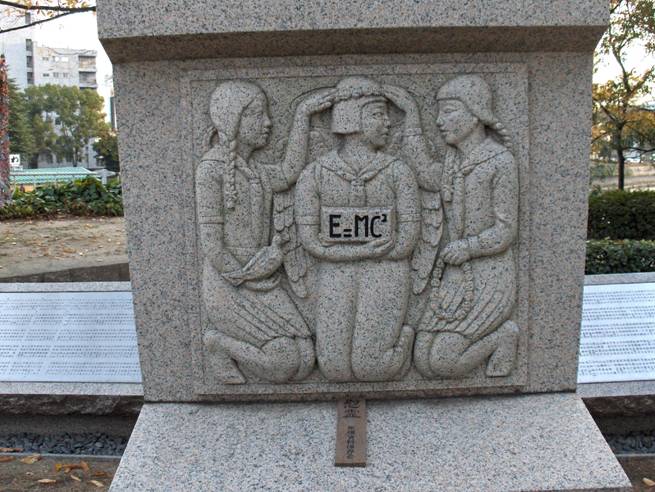

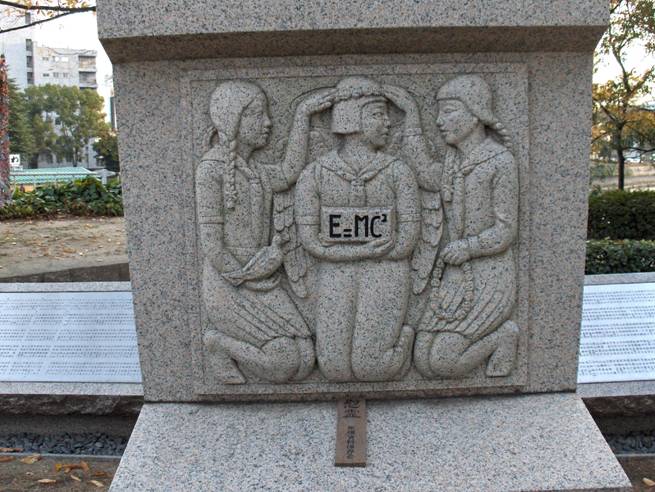

The Japanese government would not allow a memorial that mentioned the A-bomb, so this memorial depicts the equation E=MC2

This clock [left] inside the Hiroshima museum shows how many days since the first bomb was dropped, and how many days since the last testing of a nuclear bomb.

Mito Kosei, Dona and Stephan [below].

Return to

Hiroshima story -- Mito Kosei and his family

Return to Diary from Asia

Return to this story in the Diary from Asia

Return to home page