Hiroshima story -- Mito Kosei and his family

In February, 2009 our guide at the Hiroshima Peace Park, Mr. Mito Kosei [see story in Diary from Asia], received an award from the Hiroshima International Cultural Foundation, shown in the photo to the right. The Foundation presented awards to two groups and two individuals to honor their efforts to promote international relations.

Because of his strong belief that everyone should know what happened in Hiroshima, Mr. Mito became a volunteer guide in the Hiroshima Peace Park in 2006, when he retired as a high school English teacher.

He has guided 46,300 visitors (including 9,500 foreign visitors from 115 countries).

He is now

teaching trainee guides how to guide in Japanese and English, and has a wonderful blog filled with information, stories and pictures.

Mr. Mito sent us the story that his mother, Mrs. Mito Tomie [shown in the photo below], had written about that fateful day when the bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

Mr. Mito said, "Please read her story and remember Hiroshima."

During the war, Mrs. Mito Tomie (left) and her husband Mr. Mito Yoshio lived in the center of Hiroshima. Near the end of the war, the inhabitants who lived there were ordered to

move away to the country, because it was considered very dangerous to live there.

So three months before the bombing, Mrs. Mito and her husband went to live with her parents in a village about 7

kilometers away, on the other side of a small mountain from Hiroshima.

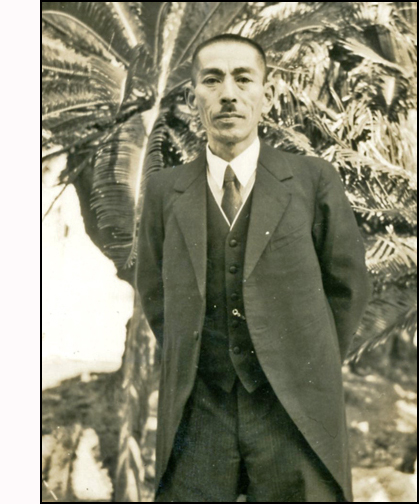

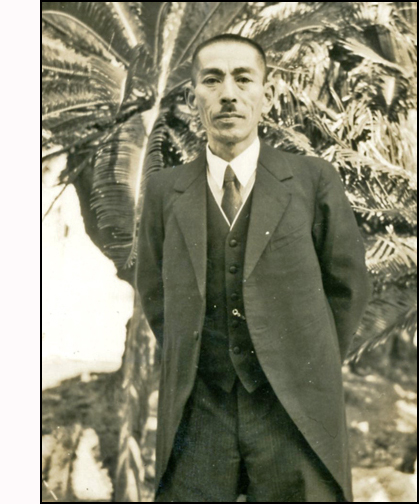

Every day, her husband and her father, Mr. Anada Hoichi (pictured to the right), and many of the people in the village went

into Hiroshima to work. Mrs. Mito was four months pregnant at the time the bomb was dropped.

During the war, Mrs. Mito Tomie (left) and her husband Mr. Mito Yoshio lived in the center of Hiroshima. Near the end of the war, the inhabitants who lived there were ordered to

move away to the country, because it was considered very dangerous to live there.

So three months before the bombing, Mrs. Mito and her husband went to live with her parents in a village about 7

kilometers away, on the other side of a small mountain from Hiroshima.

Every day, her husband and her father, Mr. Anada Hoichi (pictured to the right), and many of the people in the village went

into Hiroshima to work. Mrs. Mito was four months pregnant at the time the bomb was dropped.

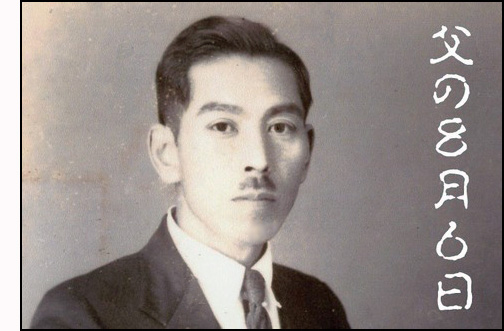

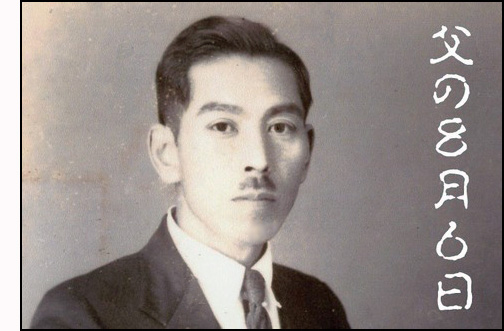

My Father's Sixth of August, 1945 in Hiroshima, Japan

by Mito Tomie

That day, fifty-eight years ago, is something I still can't forget.

It is also something I certainly don't want to remember or talk about. Even if I do talk about it, no one can feel what it really

means. I don't want to think about it. It makes my heart ache. However, if I don't want it to ever happen again, it seems wise that I should write it down somewhere.

The roar from the B-29 on that day was unlike the regular ones - it was deep and strong, as if it shook my gut. It was just as I came out of my house, I saw a huge black aircraft disappearing towards the west, barely above Mt. Gosaso. There was a tremendous explosion and the ceiling in my house and the soot fell to the ground, scattering ash everywhere. The paper sliding doors and mesh windows have not been straight since then. I only discovered this long afterwards.

Some time passed, and we received information that there was a fire in the middle of Hiroshima city, but I still didn't believe what I had heard. "It couldn't happen," I told myself but at the same time, my heart was beating fast since I knew that because we were in the middle of a war, it really could happen. This might have been how my neighbors felt, I guess, as we all walked up to a nearby mountain. No one spoke a word, we just quickly made our way up. The mountain was where we went on the 3rd of April every year with packs of food for Hanami, to see the cherry blossoms. From the very top, we could enjoy a view of all of Hiroshima city. What we saw on this day, however, was literally a sea of fire over the entire city.

Every one of us felt numb, our feet were rooted to the spot, shaking without even a word or noise. This could not be happening. Just could not. Some time later, people came back to their senses, and started to feel anxious about their husbands who had left for work this morning. We started to walk back home. Still in silence.

Soon the news about the victims spread to each of us in our quiet village. We gradually discovered who had been injured or burned. None of us knew what to do or how to be of any help. While we were too overwhelmed to help, people who were injured started to be sent on trucks to schools and temples.

I did not eat. No, as a matter of fact, I did not remember to eat. All I could think of was how my father and my husband were. I realized it was becoming dark already. No one in my family said, "They might have been burned to death" though that was going round and round in each of our hearts. We just walked here and there, in and out.

We had lights outside but they were only dim. At around nine at night, in the dim light, there was a voice saying, "I'm home!" I rushed to the entrance to find it was my father. "Ghost" is how people might express what I saw. He was covered with black on his face, or his head, I couldn't tell which. What seemed to be his clothes were torn apart and fell to the ground. It seemed as if he was covered by wrinkled wakame (dried seaweed). Even his trousers were like that, and I could see through the holes in them that his skin was also covered with something black. Even so, he was alive and was now safely home, so I was relieved.

We had lights outside but they were only dim. At around nine at night, in the dim light, there was a voice saying, "I'm home!" I rushed to the entrance to find it was my father. "Ghost" is how people might express what I saw. He was covered with black on his face, or his head, I couldn't tell which. What seemed to be his clothes were torn apart and fell to the ground. It seemed as if he was covered by wrinkled wakame (dried seaweed). Even his trousers were like that, and I could see through the holes in them that his skin was also covered with something black. Even so, he was alive and was now safely home, so I was relieved.

My husband, however, did not come home that night. Not knowing how to look for him, time just passed and I worried all night long. He did not come home on the following day either. Two days later, he finally came home. He was a teacher and was safe as he was at the bottom of a school stairwell when it happened. He told us that he couldn't come home as he had to help his students.

When the city was bombed, my father [Mr. Anada Hoichi, shown in the photo to the right] was on his way to work, only about 600 meters from the hypocenter. When the bomb exploded, he was buried alive with debris. His memory about time was not clear, but when he finally managed to push his head above the debris, some students who were in the town because of Gakutodouin* pulled him out. He then walked, avoiding the fire, and a woman he didn't know offered him her umbrella, saying, "Please take this. It's too hot out here." Taking the umbrella, he walked for half a day to come back home.

He was so glad that he survived, and told our family and neighbors that it was a narrow escape. We counted his injuries though, and found nineteen. He also had some pain on his body, so he went to see a doctor. About ten days later, small red spots -- each of them was the size of a chestnut -- appeared over his entire body. The chief doctor at National Hataka clinic said that it was the effect of the poisonous gas from the atomic bomb, and unfortunately he did not have any medicine. Still, the doctor suggested that blood exchange might help, and we tried several times with his son's blood. His body got weaker and weaker, however. Something, like guts from a fish, came out when he vomited and in his diarrhea. It filled several washing bowls. When this happened, it seemed as if all the guts in his body had been forced out. What came out gave off a horrible smell, which filled the air for a very long time.

Day after day, he became weaker, too weak to move or eat. We heard that grilled worms from chestnut trees would be good for his throat. So we actually cut the trees and grilled the white worms we found, which he still could not eat. That was all we could do, as in those days there was not much medicine available to ordinary people like us. At last he lost his voice. After that we tried to communicate using a pen, but he was too weak to hold it. He became weaker. Three days before he died he told us to fetch a parcel wrapped in a purple cloth from the second drawer in his bookshelf, which we did and showed to him. Inside was money he had withdrawn from his own bank account. Then he told us to separate it and give it to our relatives and his close friends who had meant so much to him.

On the morning of the 3rd of September, he wanted us to help with changing his pajamas as he wanted to hear the seven o'clock news. We changed his underwear and put the futon higher on his back so that he could sit straight up. He was listening to the radio with both hands on his lap and his eyes closed, looking so beautiful. The news was about the Instrument of Surrender which had been signed on the USS Missouri only the previous day. The broadcast finished at twenty-five past seven. At the very same time, my father's heart stopped. It was such a beautiful last moment of his life, so apt, so suitable for my father's meticulous character.

*Gakutodouin -- To compensate for the lack of workers, students aged more than 12 years either volunteered, or were forced, to work for the war effort, mainly in factories.

Postscript, March 8, 2009 --

Not realizing that there was radiation in the city, Mito Tomie entered Hiroshima three days after the bomb was dropped to see what happened to

their house. She was 4 months pregnant with her son Kosei. Mito Kosei was born in January, 1946. He

was very sickly in his childhood, and was absent from school for almost a month suffering from many kinds of infectious diseases, which might have been because

of a weak immunity. [Click here to learn about the survivor certificates.]

Mito Kosei writes, "My mother had bladder cancer 12 years ago, but luckily she got

well. Three years ago she suddenly had a high fever and severe pain

in the back because of a

certain virus. She was in the hospital almost half a year and confined to bed for more than 4 months, and at one point she could not stand up because of weak

muscles. Her doctor said it would take her at least half a year

before she could go shopping, but she naturally has a strong mind, and she worked hard

to exercise for rehabilitation for two months

in the hospital, and three months after leaving the

hospital she was able to go shopping in

Hiroshima. Now, at age 90, she is very well and looks much younger.

"Physically, my father remained very healthy, except for the last year of his life when he was senile

and had diabetes. He died 7 years ago at the age of 92.

"My father never told us anything about what he experienced. All his life, he kept silent

because of the emotional trauma. The survivors never got any treatment to deal with this mental stress and even today, more than 60 years later, very few of the survivors can

tell their stories to others.

"When I decided to be a guide at the Hiroshima Peace Park, I asked my mother to write a testimony of the experience,

at least about her father. But because of the emotional trauma, it took her half a year to even start

writing, and she needed another half year to finish it. She still does not want to ever write about what she saw when she entered Hiroshima

three days after the bomb was dropped.

I am ready to write whatever I know about what happened to my family."

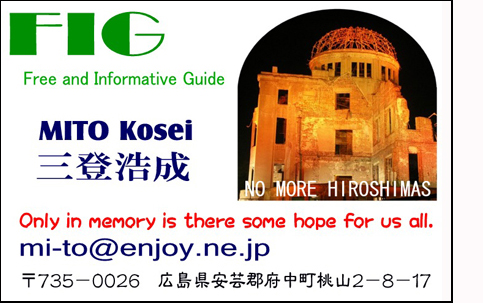

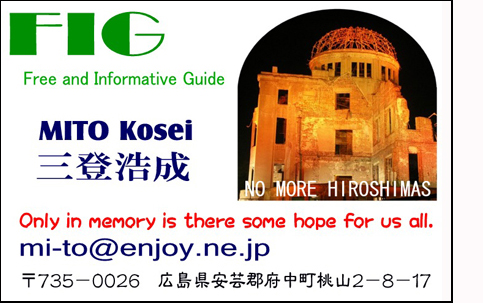

If you go to the Hiroshima Peace Park today, Mr. Mito is ready to guide you at no cost. Right now (March, 2009) there are 10 "Free and Informative Guides" (FIGs) there.

Mr. Mito's new card has his favorite words, which are from a message written at the Peace Memorial Museum by Nobel Laureate and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel in 1995:

If you go to the Hiroshima Peace Park today, Mr. Mito is ready to guide you at no cost. Right now (March, 2009) there are 10 "Free and Informative Guides" (FIGs) there.

Mr. Mito's new card has his favorite words, which are from a message written at the Peace Memorial Museum by Nobel Laureate and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel in 1995:

"Only in memory is there some hope for us all."

Pope John Paul II expressed a similar sentiment:

"War is a work of man.

War is destruction of human life.

War is death.

To remember the past is to commit oneself to the future.

To remember Hiroshima is to abhor nuclear war.

To remember Hiroshima is to commit oneself to peace."

. . . Hiroshima, February 25, 1981

Return to Diary from Asia

Return to photos from Hiroshima

Return to home page

Hiroshima story -- Mito Kosei and his family

Hiroshima story -- Mito Kosei and his family

During the war, Mrs. Mito Tomie (left) and her husband Mr. Mito Yoshio lived in the center of Hiroshima. Near the end of the war, the inhabitants who lived there were ordered to

move away to the country, because it was considered very dangerous to live there.

So three months before the bombing, Mrs. Mito and her husband went to live with her parents in a village about 7

kilometers away, on the other side of a small mountain from Hiroshima.

Every day, her husband and her father, Mr. Anada Hoichi (pictured to the right), and many of the people in the village went

into Hiroshima to work. Mrs. Mito was four months pregnant at the time the bomb was dropped.

During the war, Mrs. Mito Tomie (left) and her husband Mr. Mito Yoshio lived in the center of Hiroshima. Near the end of the war, the inhabitants who lived there were ordered to

move away to the country, because it was considered very dangerous to live there.

So three months before the bombing, Mrs. Mito and her husband went to live with her parents in a village about 7

kilometers away, on the other side of a small mountain from Hiroshima.

Every day, her husband and her father, Mr. Anada Hoichi (pictured to the right), and many of the people in the village went

into Hiroshima to work. Mrs. Mito was four months pregnant at the time the bomb was dropped.

We had lights outside but they were only dim. At around nine at night, in the dim light, there was a voice saying, "I'm home!" I rushed to the entrance to find it was my father. "Ghost" is how people might express what I saw. He was covered with black on his face, or his head, I couldn't tell which. What seemed to be his clothes were torn apart and fell to the ground. It seemed as if he was covered by wrinkled wakame (dried seaweed). Even his trousers were like that, and I could see through the holes in them that his skin was also covered with something black. Even so, he was alive and was now safely home, so I was relieved.

We had lights outside but they were only dim. At around nine at night, in the dim light, there was a voice saying, "I'm home!" I rushed to the entrance to find it was my father. "Ghost" is how people might express what I saw. He was covered with black on his face, or his head, I couldn't tell which. What seemed to be his clothes were torn apart and fell to the ground. It seemed as if he was covered by wrinkled wakame (dried seaweed). Even his trousers were like that, and I could see through the holes in them that his skin was also covered with something black. Even so, he was alive and was now safely home, so I was relieved.

If you go to the Hiroshima Peace Park today, Mr. Mito is ready to guide you at no cost. Right now (March, 2009) there are 10 "Free and Informative Guides" (FIGs) there.

Mr. Mito's new card has his favorite words, which are from a message written at the Peace Memorial Museum by Nobel Laureate and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel in 1995:

If you go to the Hiroshima Peace Park today, Mr. Mito is ready to guide you at no cost. Right now (March, 2009) there are 10 "Free and Informative Guides" (FIGs) there.

Mr. Mito's new card has his favorite words, which are from a message written at the Peace Memorial Museum by Nobel Laureate and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel in 1995: