Risk Analysis for Crossing a Street with a Situation of Uncertainty

I was asked to provide orientation to Gallaudet University's campus for two students who each are blind and have a hearing loss. To get from their dorm to their classrooms and back, they had to cross a two-lane street, shown in the pictures below. From the east, traffic has a stop sign at the crosswalk, and traffic from the west comes either from a stop sign about 40 feet away from the crosswalk, or from a parking garage on the north side of the street, about 30 feet away from the crosswalk.

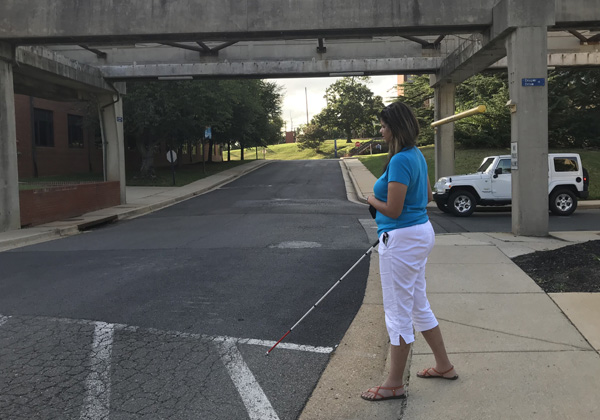

- These pictures show AJ at the crosswalk with the stop signs and parking garage exit.

We will look at the analysis of one of the students - AJ, who goes by the pronouns they/them.

We were concerned only with the risk from drivers from the west because drivers coming from the east have to stop at the crosswalk. We followed the Risk Analysis Checklist, which starts by asking whether pedestrians have the right of way to cross there (they do!), and then considers the likelihood that as AJ starts to cross, there would be a vehicle coming that would hit and seriously injure them. Here's what we found:

1. How likely would AJ be surprised by a vehicle while crossing? [It is more likely with high traffic volume and short warning times of approaching vehicles]

- Warning time: Very short: AJ could not hear some approaching vehicles until the vehicles were passing in front of them.

- Traffic volume: Very low - only about 2-3 vehicles every 5 minutes.

Conclusion: AJ thought it was unlikely a vehicle would be approaching while they were crossing at that time because, even though AJ didn't have much warning of approaching vehicles, there were very few of them passing there. AJ realized that this would not be true at other times of the day, for example when students and staff are heading home.

- Speed of drivers? very slow (they just came from a stopped position)

- Drivers expecting pedestrians? with a painted crosswalk and hundreds of students crossing there every day, pedestrians are highly expected.

- Visibility? it was daytime, so there was good visibility except for drivers coming from the garage -- as they wait to enter the street, their view of pedestrians at the crosswalk may be blocked by a post, but they can see the pedestrians as soon as they come out of the garage.

- Road conditions? Good.

- Group of pedestrians crossing with you? Probably not at that time of day.

- Multiple threat? No; there is only one lane from each direction.

- Pedestrian waiting with foot/feet in the street? AJ was comfortable waiting with a foot in the street (as demonstrated in the pictures below).

- Pedestrian using a white cane? Yes

- Drivers' community/culture? [Do drivers in that community tend to yield to pedestrians?]

- To answer this question, I normally rely on people's experience but in this case, I decided to do a little experiment to find out how consistently drivers yielded to pedestrians with white canes at that crosswalk, so I took a cane and tried it myself.

I waited to step forward until after the drivers had pulled out of the garage or stop sign and were moving toward me. There happened to be a worst-case scenario at the time because a minivan had parked illegally for a few minutes between the crosswalk and the garage, blocking the drivers' view of me when I crossed from the north side, so that they couldn't see me until I had taken a few steps into the first lane.

When crossing from the south - I tried it with two drivers coming from the stop sign, and two from the garage. They all stopped for me, one even honked and rolled down her window to tell me I could cross.

When crossing from the north (stepping out from behind the minivan) - I tried it with two drivers coming from the stop sign and one from the garage. One driver stopped as soon as I was visible. The other two continued moving but both of them stopped before reaching me, to allow me to cross.-

How likely will the drivers yield? The only characteristic that indicated the drivers would not be likely to stop was that AJ would probably be crossing alone.

All the other characteristics indicated the drivers would be likely to yield: they were moving slowly and expecting pedestrians; visibility and road conditions were good (after the minivan left!); there was only one lane approaching from that direction; AJ always used a cane and was willing to wait with a foot in the street; and we observed that when drivers were presented with a pedestrian crossing with a cane, they stopped.

We therefore concluded that it was highly likely that the drivers would yield to pedestrians with white canes.

The characteristics listed in the Risk Analysis Checklist which research indicates affect the likelihood that drivers will yield are:

- Using the chart in the Risk Analysis Checklist, we concluded that the likelihood that AJ would be seriously injured or killed if they are hit by a car going at the speed vehicles travel there is less than 20%.

I explained that the conclusions we made apply only to the conditions that existed when we analyzed it. For example, the road may become icy; the visibility may not be good at night or in the fog; and the traffic volume is likely to vary at different times of the day. Deafblind people who cannot gather the information needed to assess risk can get help to do that. Meanwhile, I gave AJ a street-crossing card that they can use to get assistance if they determine that the risk has become unacceptable, and showed them how to use it.

-

The first picture shows AJ standing at the crosswalk with a white cane and one foot in the street.

After they start to cross, a vehicle pulls out of the garage and waits.

Additional strategy: Because deafblind people may not be able to detect vehicles close to them, when they start to cross there may be a driver who is too close or fast to be able to stop for them. I suggested to AJ that it might be good to alert the drivers a few moments before they start to cross, to allow these drivers time to pass. One strategy is to take a step forward while moving the cane side to side (or just raise or move the cane without moving forward), and then pause before resuming the crossing. AJ practiced it a few times and did it well.

Return to Risk Assessment and Decisions

Return to home page