From the Metropolitan Washington Orientation and Mobility Association Newsletter, March 1992

[Updates and Editor's notes inserted in brackets]

Cane Technique: Tricks of the Trade

When I first learned how to use a cane, I didn't know why it was important to keep the hand centered, be in step and in rhythm, etc. It has only been after many years of observing what happens when people

don't use it correctly that I have discovered the importance of each aspect of the technique. I also have picked up some secrets for teaching it.

For those of you who already know them, please bear with me while I share what has taken me so long to learn!

What the Cane Will Miss:

I thought that a person who used a cane correctly could reliably avoid all obstacles below the waist. I now tell my clients that even when using the most precise cane technique, there are two things that they might not detect:

1. Objects or holes as large as a purse (with an area about 1-2 square feet);

2. Poles or corners (walls, planters) that can impact the user's shoulder or side.

Rationale for Important Aspects of Proper Cane Technique

Centered Hand

The original reason for having the hand centered may have been to have the arc cover both sides equally. However, I discovered that people who hold the cane off center will sometimes walk into poles with their face, even when their arc is covering both sides.

This is because normally, the tip of the cane may miss a pole or the edge of a wall by an inch.

If the pole is directly in front and the hand is centered, after the tip misses it, the shaft of the cane will hit it on the next swing.

The only poles that wouldn't be hit with the cane shaft are those that are too far to the side (in front of the shoulder). When the hand is off center, the shaft of the cane can also miss poles that are directly in front [Editor's note: see illustration below and examples].

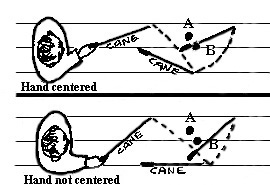

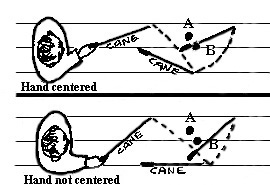

Drawing to the left shows positions of the cane shaft while person takes 3 steps toward poles:

With hand centered (top drawing):

Pole in Position "A" isn't detected and bumps shoulder. Pole at "B" is detected with shaft of cane.

With hand not centered (bottom drawing):

This cane never touches either pole. Pole in position "B" will hit the person in the face.

Being in Step and Rhythm

When people touch the cane in front of their leading foot and approach a drop-off at an angle, it is possible for the foot to step off at the same time that the cane drops off the edge [Editor's note: see example].

Arm Position and Movement

The main advantage of moving the cane with the wrist, and not moving the arm, is to feel when the cane drops off an edge. The wrist is more sensitive to a change

in position than the shoulder or elbow. If the cane drops and the whole arm moves, it can be difficult to feel the arm drop. If the arm doesn't move, that same drop causes a bigger change in the angle of the wrist than it would at the shoulder or elbow, so it is easier to notice.

When clients have difficulty detecting drop-offs, we stand near an edge, and they move the tip from the top to the bottom (keeping the arm still) until they notice the change in their wrist position.

With their attention now on the wrist, they practice approaching drop-offs until they can notice even the small ones.

For practice, I search for communities that still have curbs at the corners (high ones at first, then shorter ones). I then make sure they can also notice drop-offs that are unexpected.

[Editor's note: since there are very few communities with curbs today, I now have them practice walking along the fronts of strip malls, approaching the curbs at the ends, trying to find places where the end of the building is not too near the curb so they are less likely to use echolocation to expect it.]

There are two reasons why it is important to hold the arm out with the hand waist-high. If the arm is too low, when the cane gets stuck or jams into an obstacle, the client may get speared!

To demonstrate this, I stand next to the beginners and ask them to hold the cane properly. Then I explain that I will gently kick the tip of the cane toward them with the side of my foot.

If all goes well, their arm stays straight and the cane is pushed up and out of their way to a more vertical position.

I then ask them to hold the cane lower, and I carefully push the tip towards them again.

This time they can observe how the cane would have plunged right toward their gut (or more sensitive parts of the anatomy!).

The second reason that the cane should be held waist-high is that the more vertically that you hold it, the more easily you can feel when it drops off an edge (even at a small curb or short step).

To illustrate this principle, let's exaggerate and imagine a person walking while holding the cane nearly vertically (like a ski pole).

It would then be a cinch to feel the cane drop even over a short curb. Now imagine walking with a 30-foot cane so it is almost horizontal, or walking with a normal cane held almost against the ground.

The cane may not even drop at all when the tip passes the edge.

To be more vertical, the cane should be held as high as the waist, and it cannot be too long.

Length of cane

The above rationale is the main reason that I object to NFB's contention that the longer the cane is, the better!

It should be long enough to reach one step ahead of the client, which usually means it is about chest high.

After training and practice, when clients are able to walk confidently at their normal pace, I have them walk briskly down a hall. I watch where the tip of the cane lands, then watch their next footstep.

If the foot lands anywhere beyond where the tip was, I recommend a longer cane. However, sometimes the problem was not the cane length, but the fact that they were holding the cane too close to their body.

Kenneth Jernigan wrote in the February 1992 Braille Monitor, "The quality of one's travel skills ... is reflected in the length of one's cane and the dexterity with which one uses it ...

[The] cane should come up to the chin. Faster walkers will want somewhat longer canes."

To achieve this length he suggests that cane users gradually increase the length of their cane, beginning with a cane that is 2-4 inches longer than their customary cane.

"[As] one's skill and confidence increase, one will instinctively replace each cane with a longer one until the right cane length is achieved."

When I am teaching clients who were trained to use a cane that is longer than chest-high, I check to make sure they can dependably detect small drop-offs (2-3 inches).

If not, I make sure they are moving only their wrist and holding their hand as high as their waist, and I may also recommend that they use a shorter cane.

Jernigan suggests that longer canes will "increase the amount of information obtained." However, as I've explained, it can also decrease sensitivety to drop-offs.

Perhaps if clients could not react quickly enough to danger when using a cane that extends only one footstep ahead of them, a longer cane would be helpful.

During my 20 years of teaching, however, I have never had clients who needed the cane to reach more than a step ahead to warn them of danger.

Perhaps this is because they recieved extensive training in the precise operation of the cane, as described in this article, so they could immediately and reliably detect drop-offs and obstacles.

Another reason to not have the cane any longer than needed is that longer canes, because they are more horizontal, are more likely to go under obstacles such as chairs and railings, rather than hit the front of them.

Once they've gone under, they can also be more difficult to extricate than a shorter cane.

Arc Height

If the arc [of the cane tip] is no more than an inch or two above the ground, people will notice raised cracks and short steps more readily.

When practicing obstacle detection, to see if they have the tip low enough, I use objects that are only a few inches high (but wider than a purse! [Editor note: meaning wider than their arc]).

If the tip of their cane goes over the object, they need to bring it down more. Later, whenever the tip goes over a curb, I again point out the importances of keeping the tip low.

Tricks for Teaching

Teaching Rhythm

Some clients have great difficulty moving the cane in rhythm. I have them put down the cane and walk while clapping their hands or patting their hip in rhythm with their steps. I will either guide them while doing this or have them walk unaided,

whichever is more comfortable for them.

Once they can keep a consistent rhythm, they try it with the cane.

At first they practice just tapping the cane in front as they walk, then later move it in an arc while in rhythm.

Teaching People to Use Vision and Cane Together

For many years I pondered how to teach people who have functional vision to pay attention to the cane as well as the vision.

It isn't easy to set up good learning conditions, such as an unfamiliar places with lighting so that they can see some things but not others.

Finally I heard about about using partial occlusion, and it works great!

Once these clients are proficient with the cane technique itself and are ready to learn to pay attention to what it tells them, I have them walk with glasses that obstruct the bottom of their vision.

I cut paper to fit, and tape it along the bottom half of their eyeglasses or a pair of sunglases.

Then they wear the glasses while walking through an obstacle course or toward stairs.

It is extremely effective for enabling people to practice paying attention to the cane while also using their vision.

As they become proficient, I give them visual tasks to do while they are negotiating obstacles and drop-offs.

Stepping around the cane

Some people get into a nasty habit as they learn to use the cane. When they encounter an obstacle, they keep the cane in contact with the obstacle while they step around it.

The danger of this is obvious, and I tell them the story of the person who encountered an obstacle (a ladder), stepped to the side, and fell into the manhole from which the ladder protruded.

I also tell them about people who repeatedly fall off curbs because they keep sidestepping poles without checking.

Teaching the cane to reluctant clients

Some people don't want to be seen with a cane, and avoid learning to use it. A few of them don't really need a cane because they can see well enough, or they can learn to view eccentrally or scan.

The cane should be a tool, not a symbol, so I don't suggest they learn to use it if they don't need it.

When people say that using a cane makes street crossing safer, I cringe. I believe that using the cane can make crossings more dangerous if people think they can relax their vigil when they carry a cane.

As long as they understand that most drivers ignore the implications of the cane, it may be helpful to carry it as identification for those drivers who do respect it.

However, people who can't reliably see obstacles or drop-offs, or who must concentrate on the ground to avoid falling, do need a cane.

Those who are unwilling to consider a cane are usually willing to learn to walk comfortably with a guide, holding the door for themself and for the guide, etc.

As an itinerant [O&M instructor], I find empty buildings, such as churches, in which to teach these skills.

After they learn to be confident and poised while being guided, and learn to trust me as an instructor, they are usually willing to try the cane "just for the heck of it."

Working in the privacy of the quiet, almost empty building, they seem more willing to try it than they might otherwise have been.

Once they learn how to use the cane to detect unexpected dangers reliably, they are usually hooked!

For them, a cane is no longer just an awkward, worthless symbol that people keep insisting that they carry, but a reliable tool.

One man who was initially reluctant told me that now his cane is his "best buddy"!

Clients have said that now, when they go into shopping malls where they used to walk uneasily and fearfully, they walk with confidence.

Jernigan, Kenneth (1992). Associate Editor's introduction to Allan Nichol's "Why Use the Long White Cane?" The Braille Monitor, The National Federation of the Blind,

Vol. 35, No. 2

Return to Home page