|

Number of passersby (N=41) |

|

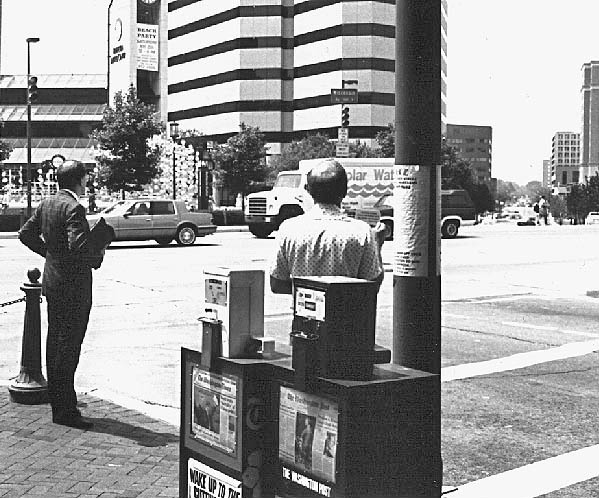

| 11 | Did not see or notice person and card. (Of these, 3 noticed the participant but not the card.) |

| 9 | Not paying attention, engrossed in conversation, or seemed not to care. |

7 |

Saw the participant and the card but concluded that he or she did not need help. Almost all reported that they would have helped had they known. |

| 4 | Could not understand English. |

3 |

Unsure what to do. (These people appeared to be very concerned while passing the participant, but were hesitant to approach, unsure whether assistance was needed.) |

| 1 | In a hurry. |

| 1 |

Not going the same way as the participant (This person asked someone to help the participant across.) |

| 1 | Other people were there who could help. |

| 4 | Reason not recorded, or the passerby refused to speak to the interviewer. |

|

Knowledge of deafness and reasons for knowing

|

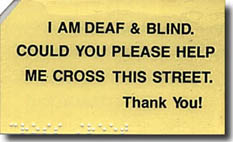

Experimental card

|

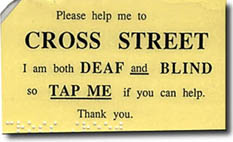

HKNC Card

|

Total

|

|

Number knowing and not knowing that participant was deaf

|

|||

|

Didn't realize person was deaf

|

5

|

4

|

8

|

|

Knew person was deaf

|

11

|

9

|

20

|

|

TOTAL

|

16

|

13

|

29

|

|

Reasons for knowing the participant was deaf:

Number of responses |

|||

|

Saw the words "deaf" or "tap me" on the card

|

7

|

4

|

11

|

|

Participant did not respond when spoken to

|

0

|

3

|

3

|

|

Participant signed while speaking

|

0

|

1

|

1

|

|

Participant said he is deaf*

|

1

|

0

|

1

|

|

Participant's voice sounded unusual*

|

1

|

1

|

2

|

|

Received no response to verbal offer of assistance; then they read the card further

|

2

|

0

|

2

|